Newark will keep its universal enrollment system for at least another year, despite critics who say it poses a grave threat to the district by allowing families to easily opt into charter schools.

The city’s board of education voted Monday to preserve the controversial enrollment system, called “Newark Enrolls,” which lets families use a single online system to apply to most traditional and charter schools. Just two years ago, the board tried to dismantle the system, arguing that it drained students and funding from the district as it fueled the charter sector’s rapid growth.

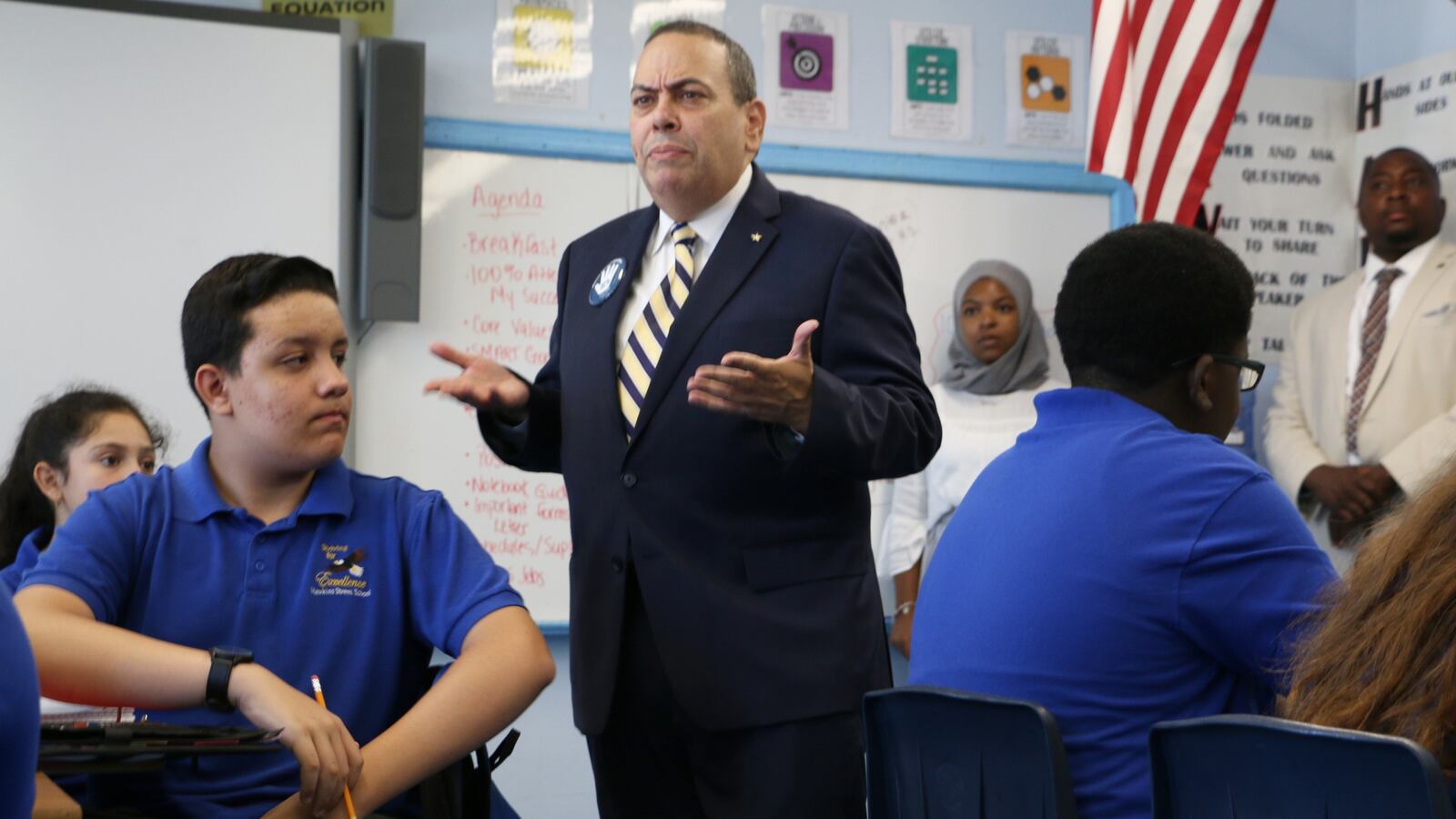

But, on Monday, the board appeared persuaded by the district’s new superintendent, Roger León, who said it is their duty to make it easy for families to send their children to whatever schools they choose — even private and parochial schools, which León said he hopes to eventually invite into the enrollment system.

“That families today go through one system and have one application makes their life a lot less cumbersome,” he said. “It’s our responsibility to make sure that whatever they choose, they get.”

However, certain key details — such as how the system will handle “overmatching,” a process in which more students than typically show up are assigned to a school to address possible attrition over the summer — appear to still be the subject of some disagreement.

León’s full-throated defense of school choice is sure to surprise some community members, who had expected the former Newark Public Schools principal to rein in the charter sector after years of swift expansion under his state-appointed predecessors. Yet León has been open about his admiration for some of the city’s high-performing charter schools and his disdain for the district’s previously decentralized enrollment system, which favored families with the wherewithal to wait in long lines for coveted district-school seats or to apply separately to multiple charter schools.

Politics also may have played a role in the current system’s survival. In recent days, charter school advocates asked state Sen. Teresa Ruiz — a Newark power broker who is close to León — to help prevent changes to the system that they oppose, according to people in the charter sector.

Newark Enrolls also may have benefited from its relative popularity. A survey of 1,800 people who used the system this year found that 95 percent were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the enrollment process. And a phone survey of 302 Newark voters last month commissioned by the charter sector found that 52 percent of respondents favored the system, while 26 percent opposed it and 21 percent were undecided, according to a summary of the results obtained by Chalkbeat.

Yet charter schools — which now serve about one-third of city students — remain a lightning rod in Newark. Critics say they sap resources from the district while failing to serve their fair-share of needy students. In March, Mayor Ras Baraka called for a halt to their expansion.

Board Member Leah Owens, a former district teacher who is critical of charter schools, argued before Monday’s vote that more was on the line than the fate of the online application system.

“This is about, What is the future of Newark Public Schools going to look like if we continue to legitimize the idea of having privately run public schools?” she said during the meeting. “When we bring these schools into our enrollment system, we are saying that this is OK and that competition will improve the schools.”

Launched in 2014, the so-called “universal enrollment” system allows each family to apply online to up to eight traditional, magnet, or charter schools. A computer algorithm then assigns each student to a single school based on the family’s preferences, available space, and rules that give priority to students who live near schools or have special needs.

In the past, the district has allowed charter schools to specify how many students they want the district to assign them. Most request more students than they have space for to account for the attrition that invariably happens as some families move over the summer or enroll in private schools.

That practice, known as “overmatching,” became a flashpoint in the recent negotiations between León’s administration and charter schools, which must sign an annual agreement to participate in the enrollment system.

León’s side revised the agreement to eliminate overmatching, according to a person involved in the talks. Some charter leaders, worried the change would leave them with empty seats and reduced budgets, considered pulling out of the system.

The threat appears to have worked. The agreement that the board approved Monday still allows for overmatching, according to people in the charter sector. (The district has not made the agreement public, and officials did not respond to a request from Chalkbeat Tuesday to release it.)

“I don’t know anything about how that happened exactly,” said Jess Rooney, founder and co-director of People’s Preparatory Charter School. “All I know is that [León] got the message that that was of great concern, and he did a lot of work to address that concern very quickly.”

Charter leaders celebrated the agreement the school board ratified Monday, which they believe protects overmatching — a process they consider crucial for filling their rosters before classes start.

However, it’s not clear that León shares their interpretation.

In an interview Monday, he said the district would only send as many students to charter schools as they are authorized by the state to serve — even if they request extra students to offset attrition. If charters lose some students over the summer, they can replace them with students from their waitlists, he added.

“The legislature determined that there is a cap that they have,” León said, “and we’re sticking with that.”

Former district officials said that relying on charter schools to fill empty seats with students from their waitlists can disrupt district schools, which may abruptly lose students whom they were assigned. But León said that was not a concern, because charters can only pull students whose top choice had been a charter school.

“They have a right to pull that student because that student is not at their preferred school of choice,” he said. “That’s fine.”

Families can begin applying to schools for next school year on Dec. 3, León said. On Dec. 8, the district will host an admissions fair with representatives from traditional and charter schools.

In the meantime, the board of each charter school that plans to participate in universal enrollment must approve the agreement. Last year, 13 of the city’s 19 charter-school operators signed on.

Michele Mason, executive director of the Newark Charter School Fund, said she would defer to the district on “the implementation question” of overmatching. Other charter leaders insisted that the issue had been settled, and overmatching would continue as it has in the past.

Either way, Mason said she expects the same number of charter schools to join this year. She added that she was heartened by León’s remarks at Monday’s board meeting.

“I really do believe he values the options that charter schools give students and families,” she said.