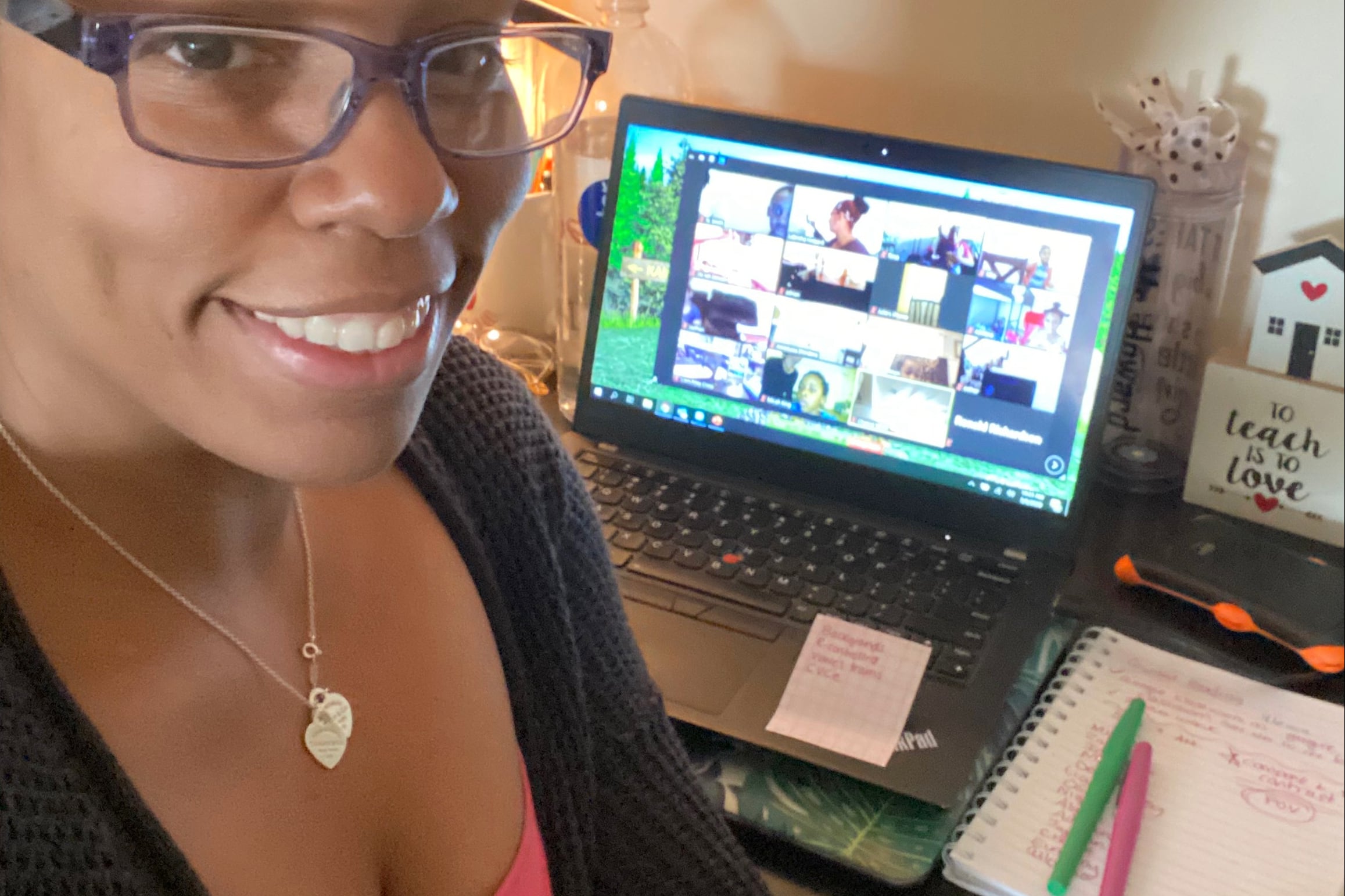

With her regular check-in calls and daily Zoom lessons, La’Krisha Howard has quickly adapted to teaching during the pandemic. Yet for this Newark educator, there are constant reminders that the new normal is anything but.

Recently, one of her kindergarten students turned up for a Zoom lesson wearing a face mask; both of his parents were infected with the coronavirus. Then Howard’s own grandmother contracted the disease caused by the virus — a calamity that Howard has tried to turn into a learning opportunity for her students.

“I’ll tell them, ‘Ms. Howard is feeling super blue today, can you help me?’ Then they’ll give me ideas that I can do, and in that they identify things that they can do,” said Howard, who teaches at Upper Roseville Academy in Newark’s North Ward, part of the KIPP charter school network. “It’s been a lesson for all of us; we’ve been learning and figuring it out as we go.”

Newark’s charter schools, which educate more than a third of the city’s roughly 50,000 public-school students, have also been figuring things out on the fly in the weeks since the pandemic forced school buildings statewide to close.

Nearly 20 different organizations run charter schools in Newark, including national networks such as KIPP and more than a dozen local operators. Functioning independently of the city’s traditional public school district, the charter schools have scrambled separately to keep students learning during the lockdown: They gave out thousands of laptops to their families, developed their own virtual learning routines, and offered online counseling.

Now, after Gov. Phil Murphy announced this week that classrooms will remain off-limits for the rest of the school year, Newark charter schools are settling in for several more weeks of virtual learning. But they are also thinking ahead to the summer and fall when they will have to help ease the psychic burden that students have shouldered during the school shutdown, while also confronting the academic regression that many students will suffer after months of virtual classes.

“We’re doing online learning, but it’s just not the same as being there with kids,” said William Mellman, principal of Great Oaks Legacy High School. “In some ways, it’s just trying to stop the bleeding.”

Offering aid amid the coronavirus

Schools are on the frontlines of the pandemic, which has dealt an especially heavy blow to Newark. As of Friday, more than 6,100 city residents had tested positive for the virus and 485 residents had died.

At Mellman’s high school, which educates just over 380 students, three students have lost family members to the virus and many others have had relatives fall ill. Many families have had to move in with relatives due to lost jobs or family members needing to self-isolate, creating cramped quarters that can distract from online learning, Mellman said.

At University Heights Charter School, which enrolls more than 900 students from preschool to eighth-grade, nearly 20% of students have reported having a family member contract the virus, said Executive Director Tamara Cooper. A similar share of staff members has become infected or had a loved one become ill; one staffer is currently in an intensive care unit.

“Some, they had it, their spouse and child had it, and now they’re recovering,” Cooper said. “Some lost grandparents, moms, dads, uncles.”

Aware of the virus’s heavy toll on Newark families, the school enlisted security guards, cafeteria workers, secretaries, and nurses to help teachers call families regularly to check in. Tonya Lloyd, who oversees mental-health services, holds virtual workshops to coach students on managing their anxiety and building resilience. Counselors offer support even in the evenings and on weekends, and the school sends cards and flowers to grieving families, knowing that many cannot attend their loved ones’ funerals due to social distancing rules.

“How do we help them get closure within their hearts after such a large loss?” Cooper said.

Meanwhile, schools have also been making sure students stay fed, either by serving grab-and-go meals or referring families to Newark Public Schools’s meal sites. The BRICK Education Network, which oversees 1,850 students in Achieve Community Charter School and Marion P. Thomas Charter School, has even provided families direct cash assistance and helped them navigate the state unemployment system.

“We cannot look at student learning in isolation,” said BRICK CEO Dominique Lee. “In times like this, there’s a hierarchy of needs.”

Learning from home

Still, schools cannot stop educating students just because they’re stuck at home.

Like the Newark school district, most charter schools sent paper assignment packets home with students when school buildings first closed in mid-March. That bought the schools time to assist the many families who lacked computer or internet access at home.

After finding that 35% of KIPP families did not have computers, staffers quickly rounded up the network’s classroom laptops so they could be loaned out, said KIPP New Jersey Executive Director Joanna Belcher. On the pickup day, families began lining up at 6:45 a.m. To date, the network has distributed more than 3,300 laptops.

Once KIPP gave out devices, it began shifting to mostly online learning in April. Since then, an average of 96% students have logged onto Google Classroom at some point each school day, the network said.

Each morning, Howard’s kindergartners gather on Zoom for lessons in phonics, reading, and math. In the afternoons, she meets virtually with small groups of students who need extra help, including those with disabilities. Still, about a quarter of Howard’s students cannot attend the live lessons because their parents are at work, so she records the Zoom lessons and calls or texts families to check in.

“Just the phone call of ‘How are you doing?’ changed a lot,” she said. “It’s like, I’m not in this alone.”

Teachers at Great Oaks Legacy High School also give morning lessons on Zoom, while AmeriCorps tutors work individually with students in the afternoons. The school shortened classes from 50 to 30 minutes to avoid “Zoom fatigue,” said Principal Mellman. But he felt it was vital for students to continue meeting face-to-face with teachers, even if that must now happen on screens.

“There’s so much power in students interacting with adults who care for them,” he said.

Looking ahead to an uncertain future

Even after loaning out laptops and moving classes online, most schools have accepted that students simply won’t learn as much remotely as they would in a classroom.

BRICK teachers are assigning work in paper packets and online, and giving lessons on Zoom. But the network decided it would be difficult to properly teach new material virtually, so much of the work is reviewing what students previously learned, Lee said.

“We’re not a virtual school,” he explained. To make up for the missed learning, the network plans to offer online summer school and add a class period next school year dedicated to shoring up each student’s learning gaps.

KIPP is also planning for virtual summer school and bracing for some students’ skills to slip during remote learning — what some educators are calling “the coronavirus slide.”

“That’s one of the hardest things for us to grapple with,” Belcher said, “because we take the promises we made to our kids really seriously.”

University Heights expects to open summer school to all students, not just those with low grades, and perhaps start next school year early. It also might offer virtual after-school tutoring this fall, as some students have actually performed better online than in classrooms where they might be distracted by their peers, Cooper said.

Most charter schools are also preparing to ramp up their mental-health services this fall — and not just for students and staff members who lost loved ones to COVID-19. The disruption and fear wrought by the pandemic has taken a toll on everyone, Cooper said.

“This will be a life-changing event,” she said. “They will always remember where they were during COVID-19.”