Even as a national debate rages about whether it will be safe to reopen schools this fall amid surging coronavirus cases in most states, some districts aren’t waiting for answers — they’re trying in-person learning now.

One of those districts is Newark, where a small number of students and teachers returned to classrooms last week for summer school after spending about a third of this past school year learning remotely. Newark had recorded more than 8,000 coronavirus infections and 636 deaths as of Tuesday, but like the rest of New Jersey, its number of daily new cases has declined since peaking in April.

The in-person pilot at two elementary schools is designed to test out safety measures — from morning temperature checks to face mask requirements to spread-apart desks — while giving the district an opportunity to make necessary adjustments before thousands more students and staffers are expected to return in September.

Just as important, the summer school programs at Thirteenth Avenue and First Avenue schools might assuage the fears of people who seriously question whether brick-and-mortar schools can operate safely during the ongoing pandemic. If the pilot avoids virus outbreaks, the district will be able to point to local examples of safe in-person learning, which might be more compelling to families and educators than scientific studies or official assurances.

“When we all come back together, now there’s going to be word of mouth. ‘What was it like? How was it? How did the kids do?’” said LaShanda Gilliam, a vice principal at Thirteenth Avenue School who runs the summer program. “And all of us who were here can attest to that. We can talk about it.”

“That makes me feel a little more confident that our families will be at ease,” she added, “and that other students will be at ease.”

Newark’s five-week summer programs began July 6, with all students attending virtual classes except for a few dozen who opted for in-person sessions at the pilot schools. Those two sites, which are following safety guidelines the state issued last month for in-person summer programs, offer a glimpse of what schools might look like this fall if some amount of in-person learning resumes, as state and local officials insist will happen.

At Thirteenth Avenue School, the 37 first-through-eighth graders whose families agreed to in-person summer classes start lining up outside the school at 8:30 a.m., Gilliam explained. A security guard makes sure they stand on freshly painted lines spaced six feet apart, per federal health recommendations.

Students then go through a four-step entry process, Gilliam said. First, they answer questions to check for COVID-19 symptoms. Next, school nurses or other staffers take their temperature using no-touch thermometers. Third, students step onto a shoe-sanitizing device. Finally, they apply hand sanitizer. Only then can they enter the building.

Before teachers open their classrooms, they check for a note affirming that custodians disinfected their rooms the previous day, Gilliam said. Then students can enter and eat bagged breakfasts at their desks. (They’re given to-go lunches when they leave at noon.)

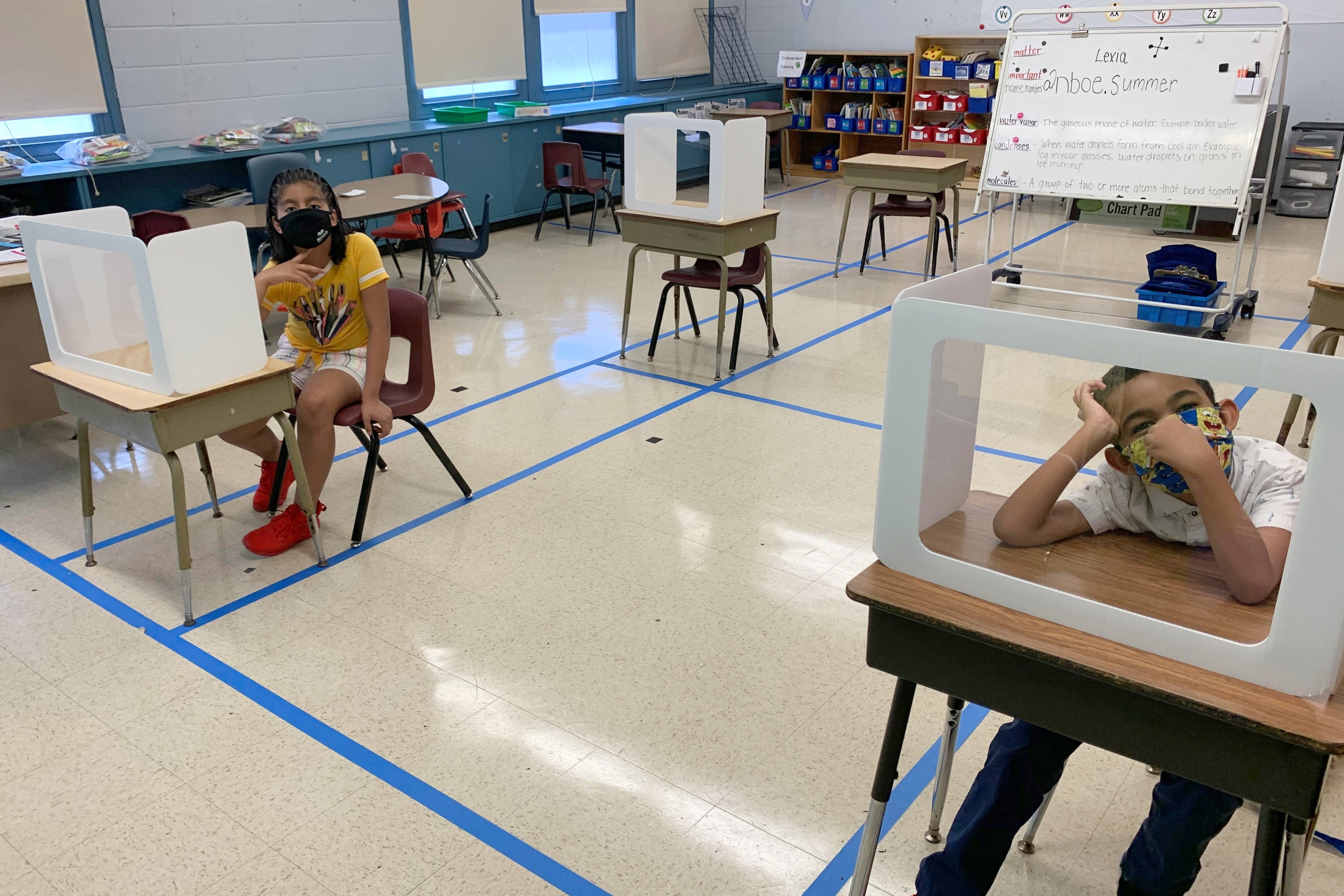

Inside classrooms, the floors are lined with blue tape to ensure desks sit six feet apart. The distancing requirements only allow for up to about 10 students per room, but the limited number of students in the summer program has kept class sizes to about six students, Gilliam said.

During class, students and teachers must wear face masks, which the school gives to anyone who needs one. The district also provided each teacher a cleaning kit with hand sanitizer, disinfectant wipes and spray, and extra masks.

Each student’s desk is topped by a three-sided barrier, about a foot high with a clear window in the front, which adds another layer of protection against airborne transmission of the virus. The barriers and physical distancing allow students to take off their masks for brief breaks, Gilliam said.

Students’ supplies are kept in separate bags to prevent sharing of materials — and, potentially, the virus. They work on laptops that are disinfected every day rather than using books or paper packets, which would be difficult or impossible to clean.

Even with the intricate safety protocols, Gilliam said that in-person learning offers advantages over virtual lessons.

“You get to see the teacher model the lesson right then and there and answer any questions right then and there,” she said. “And it’s still a little bit of socialization, even though it’s not like it used to be.”

Newark’s experiment with in-person learning comes as schools face immense pressure to reopen this fall — from some working parents, experts worried about the academic and psychological effects of prolonged remote learning, and the Trump administration, which has threatened to withhold federal funding if school buildings stay shuttered.

But many teachers and some parents have expressed alarm at reopening schools while infection rates rise in many parts of the country, leading some districts, including those in the Los Angeles, Phoenix and Nashville areas, to reverse course and keep classes online when the new school year starts.

Amid the ongoing debate, some districts have quietly reopened classrooms for summer school. That has not always gone smoothly. Summer programs in Connecticut and Iowa were suspended after individuals tested positive for COVID-19 or recorded elevated temperatures, a symptom of the illness. And in Detroit, dozens of protestors — including teachers — blocked buses from picking up students for summer school Monday, citing fears about the health risks of in-person classes.

Newark has taken pains to avoid such a backlash. Unlike in Detroit, where a couple thousand students opted for in-person summer school, only a few dozen students were given that option in Newark in an effort to keep the pilot program small and manageable. And, crucially, the in-person experiment has the support of the Newark Teachers Union, whose president said he proposed the idea to the district as a way to work out any kinks before schools reopen on a wider scale.

“You make a mistake now, you affect one teacher and maybe five or six kids in a classroom,” said NTU President John Abeigon, adding that it’s easier to isolate and contain infections among small numbers of people. “You make that same mistake in September with 38,000 kids and 3,800 instructional personnel, that’s major — there could be major ramifications.”

The Newark school district originally said all programs this summer would be virtual. But after the state announced last month that summer programs could take place in person if they met new safety standards, the district decided to pilot the two in-person sites while the majority of students took online classes.

Teachers and families at First Avenue and Thirteenth Avenue schools (and a few others that send students to those sites during the summer) were given the choice between in-person and online programs. During virtual meetings, Superintendent Roger León explained the safety protocols at the in-person sites.

That was enough to persuade Alimata Bila to send her six-year-old daughter, Grace, to Thirteenth Avenue’s in-person program.

“I said, OK, she has stayed home long enough, since March. I want her to go out and be with other kids and have fun,” said Bila, who has been working from home the past several months while caring for her one-year-old son and trying to supervise her daughter’s virtual lessons.

“Learning from home is not the same thing as coming to school every day, getting to interact with other kids and the teacher,” she said. “Those teachers went to school and received training for that — I did not.”

It remains to be seen whether the pilot programs will convince skeptics that in-person learning can proceed safely this fall. Some Newark parents and educators have already suggested they will choose to continue with remote learning, which Gov. Phil Murphy said is their right.

Still, the pilot is already providing valuable data “to inform future decision-making and help us continue to ensure the safety of every child and staff member,” Superintendent León said in a statement.

Gilliam agreed, calling the pilot “great practice” for the fall. She added that it’s lessened the burden on working parents who struggled with remote learning this spring.

“I felt like I could sense the desperation of the parents,” she said. Now, “seeing them so happy, so eager, I just feel like that’s really the point of this school.”