Up until a few days ago, IIdemar Vazquez was feeling desperate.

Her daughter Iliana’s Newark charter school recently announced that it’s starting the year virtually. As a single parent, Vazquez knew she’d have to stay home during the day to help her fourth-grader learn remotely. But when Vazquez requested different hours at the hospital where she works as a medical assistant, her bosses were unsympathetic.

“They’re putting the pressure on us,” she said. “Either we find a sitter or we pretty much resign.”

That’s when Iliana’s school came to the rescue. The BRICK Education Network, which manages the Marion P. Thomas Charter School that Vazquez’s daughter attends, said this week that it will open some classrooms for the children of essential workers and other students who aren’t able to learn from home. The schools will provide adult supervision, along with internet service and meals, so students can do their virtual learning in a safe environment while their parents work. For parents like Vazquez, the arrangement is a lifeline.

“I am a single mother, head of the household,” she said. If she had been forced to leave her job to look after her daughter, “it would be unemployment.”

Across New Jersey, a growing number of school districts have reluctantly decided to hold off on reopening classrooms until the coronavirus is more contained. In Newark, the city’s major charter school networks and the traditional school district — the state’s largest, with more than 36,000 students — made the call this month, pivoting from “hybrid” reopening plans to all-remote learning.

The news was welcomed by many families and educators who worried about the risks of in-person learning during a pandemic. But the abrupt shift to fully virtual learning comes with a cost for working parents who rely on schools not just for the education they provide, but also the child care.

Newark officials are reviewing possible sites where students could do supervised online learning while their parents work, officials said Thursday. But they could not guarantee those sites will be open by the start of the district’s school year on Sept. 8.

That has left parents who don’t have the luxury of working from home — including hospital, supermarket, restaurant, and warehouse employees — scrambling to make other arrangements for their young children. Their options are limited: pay for child care, find friends or relatives who can babysit, or leave their jobs.

“I’m stressing right now to figure out if I’m going to quit my job and sit home until November to make sure my child gets an education,” said Erica Larkins, a retail worker whose son Jay is entering the first grade at Avon Avenue School. If that happens, Larkins asked, “Who’s paying the bills?”

Throughout the country, “learning pods” have sprouted as one solution to the riddle of remote learning. A cross between child care and tutoring, the pods typically involve a group of parents hiring an educator to supervise their children’s home learning.

But private pods are unaffordable for many families. In some cases, parents must shell out thousands of dollars to join. In New Jersey, a new group offering to help parents of color form learning pods says costs will range from $150 to $350 per week, though it’s “exploring” ways to include families who receive child care subsidies.

Some cities and districts have stepped up to offer alternatives for lower-income families. Unlike private pods, the public versions are free and held in communal spaces such as libraries, recreation centers, and schools where students can take their online classes under the watchful eye of trained adults. New York City and Boston are among the cities racing to create these new pop-up child care and remote-learning centers, while school districts from Colorado to Indiana and Tennessee are spearheading similar efforts.

In Newark, Mayor Ras Baraka said during a radio interview Thursday that the city has prepared a list of public spaces where students might be able to do remote learning, such as recreation centers and libraries. Officials still must inspect the sites and establish criteria to determine which parents will be given preference for the limited number of spaces that might become available, he added during the interview on WBGO’s Newark Today.

Jaz West-Romero, a working parent with several children in Newark schools, called into the show to ask whether the sites will be open by the start of school. Newark Superintendent Roger León, who was also on the program, said the district is working hard to assess the possible remote learning sites — but he couldn’t promise West-Romero that the sites would be ready by the time classes begin.

“What I don’t want her doing is thinking this is going to be solved and she can go to work on Sept. 8, then Sept. 8 hits and I don’t want her disappointed,” León said. “But I’m working on trying to figure that out.”

The district and the mayor’s office did not respond to requests for information earlier this week.

Catherine Wilson, the president and CEO of United Way of Greater Newark, said it should not fall solely on the city and school district to solve the challenges created by remote learning. The private sector must also chip in to help families with child care and the technology — including laptops and WiFi — needed for virtual learning, she said.

“We need to come together and start solving for some of those issues,” she said, “because they aren’t going to go away overnight.”

So far, just a couple Newark charter school operators have announced plans to offer child care support while in-person classes are suspended. One of them is the BRICK Education Network, which manages Achieve Community Charter School and the three Marion P. Thomas charter schools.

While all students at the schools will begin the year virtually, BRICK will invite a limited number to do their virtual learning at school, officials said. So far, about about 70 students have been selected to attend these “remote learning centers.” The students will be grouped 15 to a classroom, each of which will be overseen by two staff members, including teachers and social workers. The students will work independently on their laptops, attending Zoom classes and completing assignments, while the adults will be available to answer questions but won’t give lessons.

The schools will serve breakfast and lunch in the classrooms, and students will likely have recess. The schools will take the same safety precautions they would have if in-person classes had not been postponed, the officials said. For instance, temperatures will be taken on arrival, students and employees will wear face masks, and students will sit 6 feet apart.

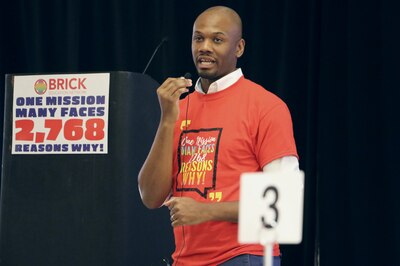

BRICK CEO Dominique Lee called the centers a community-oriented alternative to private learning pods, which will spare some parents from having to choose “between their jobs or providing a safe space for their children.”

“That’s not a choice that any parent should have to make,” he said.

This story has been updated to include information that Newark officials provided on a radio program Thursday evening.