Education took center stage in Tuesday’s closely watched elections.

That was most obvious in Virginia, where the Republican candidate for governor harnessed parents’ outrage over school closures, mask mandates, and talk of teaching students about racism in America — and rode their anger to victory.

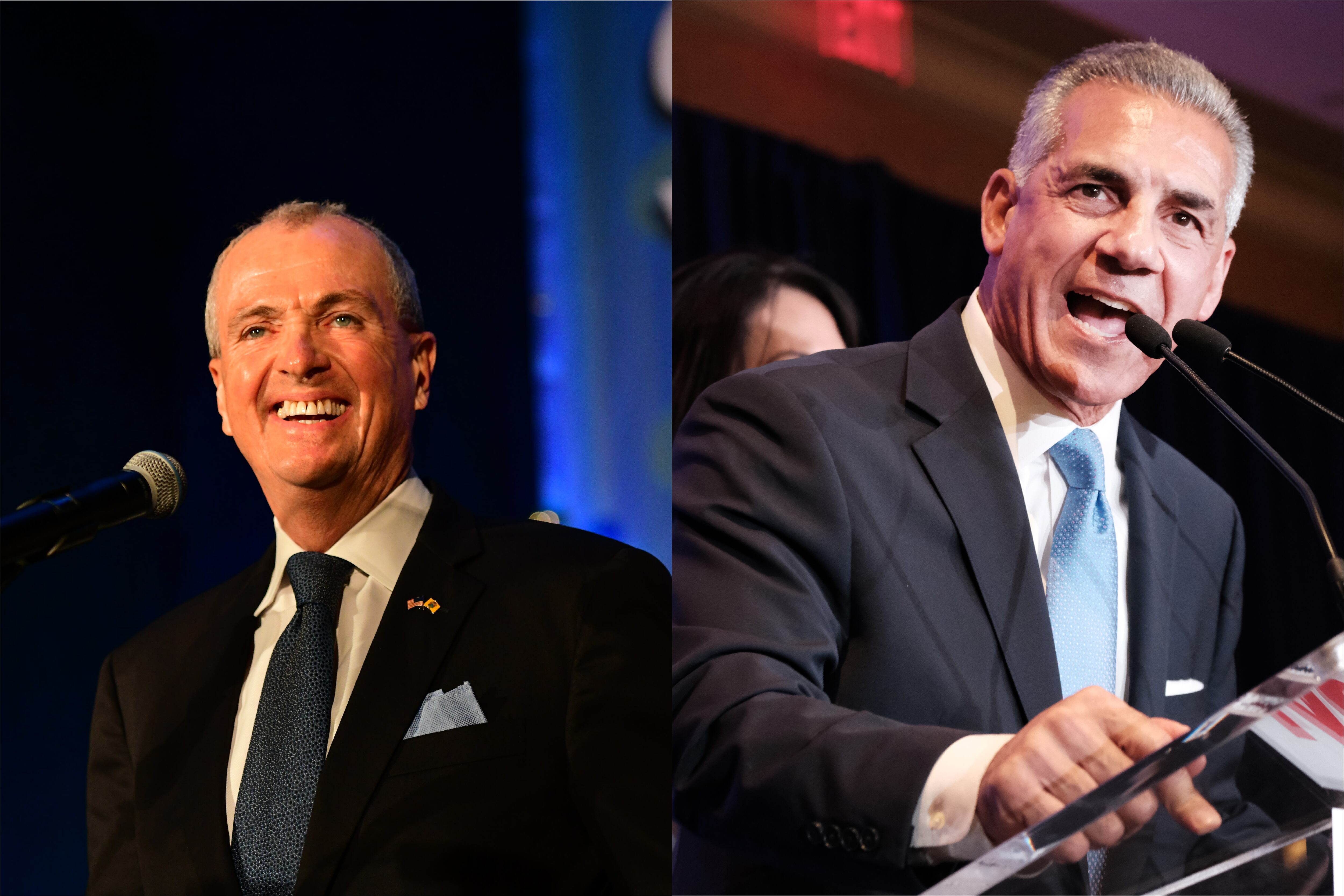

But schools also were important in New Jersey, where Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy won reelection Wednesday by a stunningly narrow margin in a state where Democrats enjoy a significant electoral advantage. While the Republican candidate, Jack Ciattarelli, largely hammered Murphy for his progressive policy agenda and stringent COVID restrictions, he also promised to lower taxes by changing the way schools are funded and said parents should decide what their children learn in school and whether they wear masks or get vaccinated.

School-fueled frustration didn’t propel Ciattarelli to victory in New Jersey, where most voters actually support school mask and vaccination mandates. But it likely contributed to his stronger-than-expected performance by motivating angry, mostly white voters to turn out on election day.

“The Trump voters were spurred on by the culture issues” in a way that “Democratic voters were not,” said Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Polling Institute, adding that the same held true for Murphy’s mask-in-school requirement. “The ones who were energized by it were the voters who were vehemently opposed to it.”

Taxes and the economy were the leading issues for New Jersey voters, according to a Monmouth poll conducted in late October. But schools ranked third, beating out the pandemic and crime.

Education policy highlighted the stark differences between Murphy and Ciattarelli, a former state lawmaker popular with many Trump supporters.

Murphy hiked taxes on millionaires, boosted funding for schools, backed a law requiring students to learn about LBGTQ figures in history, made mask-wearing mandatory in schools, and ordered teachers to get vaccinated or take weekly COVID tests.

By contrast, Ciattarelli promised to slash taxes, cap school spending, “roll back” the LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum, and end mask mandates. He also objected to teaching students about white Americans’ role in racial oppression.

“There is systemic racism, but I don’t think we should be teaching our children that white people perpetuate systemic racism,” he said during a debate. Murphy responded that students must learn “the whole truth,” which includes “slavery, oppression, racism in our country’s history.”

Ciattarelli said his policies would “empower parents” to choose what’s best for their children, echoing Glenn Youngkin, the Republican businessman who won Virginia’s gubernatorial election partly by vowing to give parents greater control over what their children learn in public school. Youngkin also tapped into parents’ residual anger about last year’s school closures, and some white voters’ resistance to teaching students about America’s long history of anti-Black racism. Ciattarelli raised similar issues, though they gained less traction in New Jersey’s race.

“It wasn’t what you saw in Virginia: ‘Let’s ban Toni Morrison’,” said Ben Dworkin, director of Rowan University’s Institute for Public Policy & Citizenship. “But, there were some folks saying, ‘There are some things I want to teach my kids at home, and I don’t want schools to do it.’”

New Jersey Republicans, with about 1.1 million fewer registered voters than Democrats, tried to capitalize on contentious school board elections to drive more voters to the polls. Republicans in the state senate released a statement Wednesday claiming that parent anger over schools helped Ciattarelli outperform election forecasts.

“Parents who are upset with the direction of their schools came out in force to ensure they have a say in what’s being taught in their children’s classrooms,” they wrote.

While school issues might have galvanized some conservative voters, analysts said that education likely did not play a decisive role in the unexpectedly tight race. They also pointed out that education motivated Murphy’s supporters, not just his critics: Most voters approved of his school mask mandate and his handling of the pandemic, and the state teachers union spent millions of dollars and organized a massive outreach campaign to help Murphy win reelection.

Despite the uncomfortably close outcome, the union claimed victory Wednesday.

“Whether it be education, public health, or the economy, residents see what has been accomplished in the last four years and trust Gov. Murphy to keep our state on an upward trajectory for the next four years,” said a statement from New Jersey Education Association President Sean Spiller.

Yet other Democrats were less celebratory.

Shavar Jeffries, president of Democrats for Education Reform, a political advocacy group that has sometimes clashed with teachers unions, said Murphy failed to present an “affirmative message” to voters outlining his vision for a second term. He said Democrats from Trenton to Washington need to explain how their policies on education, health care, and other issues will improve life for average Americans, including Black and Hispanic voters whose support the party often takes for granted.

He also argued that Murphy and other Democrats should shift the focus away from hot-button education issues, including masks and teaching about racism, to helping students recover from the pandemic.

“We ought to be having a conversation about how do we support our students so they can get up to speed,” he said, “as opposed to some of these culture war issues, which are very important, but in many ways are secondary to just the nuts and bolts of: Are students learning?”

Catherine Carrera contributed reporting.