Even before learning they wouldn’t get pandemic bonus pay, Newark teachers were fed up.

Since schools reopened this fall, worker shortages have forced teachers to take on extra students and classes while also helping clean classrooms, supervise cafeterias, and monitor hallways. Inside their classrooms, teachers face pressure to accelerate learning even as they confront a spike in student conflicts, outbursts, and meltdowns.

Meanwhile, many teachers had to toss out their usual lesson plans after the district rolled out new curriculum materials this fall. And some didn’t feel safe in their own schools while the district delayed COVID testing for months.

From May to October, 342 teachers and other instructional staffers quit or retired, according to the teachers union — a 16% increase over the same period pre-pandemic.

“This has been the most difficult year for me since I started teaching 16 years ago,” said Yvette Jordan, a social studies teacher at Central High School.

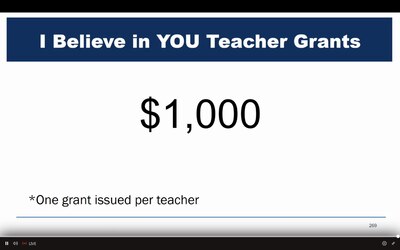

But the last straw for many educators, the moment when exhaustion hardened into anger, was when officials made clear they aren’t giving “thank you” bonuses to employees for working throughout the pandemic, as school districts nationwide have done. Instead, the superintendent of the Newark school system, which is getting well over $280 million in pandemic aid, told teachers they could complete a lengthy application for a $1,000 grant that can only be spent on classroom supplies.

“That was just a slap in the face,” said John Abeigon, president of the Newark Teachers Union, adding that some schools inexplicably rejected the applications teachers submitted. The union filed a grievance over the grants.

Unlike other unions that clashed with districts over school reopening, the Newark union has mostly cooperated with officials — until now. The pay snub, along with the staff shortages and crushing workloads, has pushed teachers to a breaking point, Abeigon said. If conditions don’t improve, he threatened to call on teachers to strike.

“We’re at a point where if something doesn’t give,” he said, “we may just have to.”

Instead of bonuses, a divisive grant

During the pandemic, many school districts have given teachers and other staffers bonuses ranging from $500 to $5,000 in a bid to boost morale and avert resignations. The money generally has come from the COVID relief packages that Congress sent schools earlier this year.

Last month, Great Oaks Legacy charter schools in Newark gave every teacher who’d stayed on the job since August a $1,000 thank-you payment. School officials said they hoped the bonuses would keep worn-out teachers from quitting over winter break.

“We just hope they come back,” said Jared Taillefer, the schools’ executive director, at a recent board meeting.

Newark Public Schools, which received an extra $86 million in state aid this year in addition to the federal money, decided against giving bonuses.

Instead, Superintendent Roger León announced in August that every teacher was eligible for a $1,000 “I Believe in You” grant for their classrooms. To access the money, they had to complete a six-part application that included a proposed project, student learning goals, a plan to continue the project after the money was spent, and an itemized budget. School administrators would assess whether the goals were challenging, the project was sustainable, and the budget was “realistic, clear, and frugal,” according to district guidance.

Teachers were livid. Instead of rewarding them for their hard work, the district was asking them to do more work just to get money for classroom supplies. In a Facebook post, the teachers union said León could “take that grant and shove it.” Many teachers declined to apply.

“You had to write a thesis to get it,” said an elementary teacher who, like others interviewed for this story, requested anonymity to avoid retaliation. “I was like, forget it.”

Adding insult to injury, schools rejected some applications, several teachers said. The educators said they don’t know why some requests for laptops, projectors, novels, and other learning tools were turned down, but they didn’t plan to reapply.

In a statement, district spokesperson Nancy Deering said officials are grateful for employees’ hard work.

“We are extremely thankful to all teachers and staff members who continue to work diligently with us during this global pandemic,” she said, adding that their efforts are why the district is “meeting and exceeding goals.”

Cascading challenges test teachers

This school year has unleashed an avalanche of challenges more trying than even those during remote learning, educators from across the district told Chalkbeat.

School conditions are tough, with face masks and desk shields still required and many water fountains shut off. Student needs are extraordinary, with many still reeling from the social and psychological upheaval of the pandemic. And learning gaps are immense, with recent tests showing that most Newark Public Schools students need intensive support in reading and math.

Then there’s the behavior issue. After more than a year and a half of learning from home, many students are struggling to focus in class, follow school rules, and interact with classmates, multiple teachers said.

“I’m only teaching 25-30% of the time and everything else is dealing with behavior,” an elementary school teacher said. “The fights at the high school level are out of control,” said a secondary school educator.

Making matters worse, school districts nationwide are facing a labor shortage. In Newark, 90 instructional positions remain unfilled three months into the school year, district officials said. Union officials say the number is higher.

The district has hired hundreds of new teachers in recent months, but many others have left. From May to October of this year, 268 instructional staffers quit, compared with 187 last year and 225 in 2019, according to the union, which also counted 74 retirements during that period this year. Last month, another 39 educators resigned and eight retired, according to district documents.

One teacher said two of her colleagues recently left for higher-paying jobs in nearby districts. Newark Public Schools’ median teacher salary of $65,618 in the 2019-20 school year is lower than several districts in Essex County, including East Orange, South Orange-Maplewood, and Montclair, according to state data.

“You’re not paying them right and you’re not giving them support,” another teacher said. “What do you expect?”

Deering said the district provides “teachers and staff with support on an individualized and ongoing basis.”

Many students have been left with substitute teachers. But when schools can’t find enough subs, administrators have assigned teachers additional students or asked them to teach extra periods.

At McKinley School, where at least nine educators have quit since September, a math teacher was given a social studies class and other staffers had to teach Spanish during their free periods after that teacher left, according to a school employee.

“If parents knew what was going on, they would be very angry,” the staffer said.

A shortage of cafeteria workers and custodians means some teachers have had to help serve lunch and wipe down desks and tables. Despite the district’s influx of funding, several teachers said that basic supplies aren’t always available.

“The district got millions of dollars to help during the pandemic and yet there’s no toilet paper or paper towels in the bathroom,” a high school teacher said. “I buy gloves, even garbage bags,” a preschool teacher added.

Teachers worry that the staff shortages and instability could set students even further behind while wearing out educators and undermining morale.

“It’s been low before, but this is the lowest of lows,” said another high school teacher. “Our goal is just to make it to winter break.”

Catherine Carrera contributed reporting.