After nearly a year of remote learning, how far have students in Newark and across New Jersey fallen behind? The answer isn’t clear — and neither is the plan for catching students up.

Nationwide data suggest the pandemic-induced learning loss could be steep. According to one analysis, students across the country began this school year an average of three months behind in math, with students of color further behind than white students. Students could end the year behind by half a grade level or more, according to the analysis by McKinsey & Co.

The picture is blurrier in New Jersey. Officials are bracing for big holes in student learning caused by the chaotic shift to remote learning last March, but they lack statewide assessment data to quantify the gaps.

In Newark, the district has not said how much learning students have lost — possibly because officials don’t have enough data to say for sure. And because schools in that district and more than 170 others remain fully remote, it’s likely students’ learning gaps are growing still.

Now, state and local officials are making plans for expensive remediation programs, such as intensive tutoring and summer school, with the state promising more details soon. But the limited learning loss data means that officials are plotting an academic recovery without a full view of the damage.

“We understand,” said acting state Education Commissioner Dr. Angelica Allen-McMillan to lawmakers last week, “that it is impossible to accelerate learning if you cannot measure it.”

Mounting evidence suggests that students nationwide entered this school year behind the typical academic starting point, particularly in math.

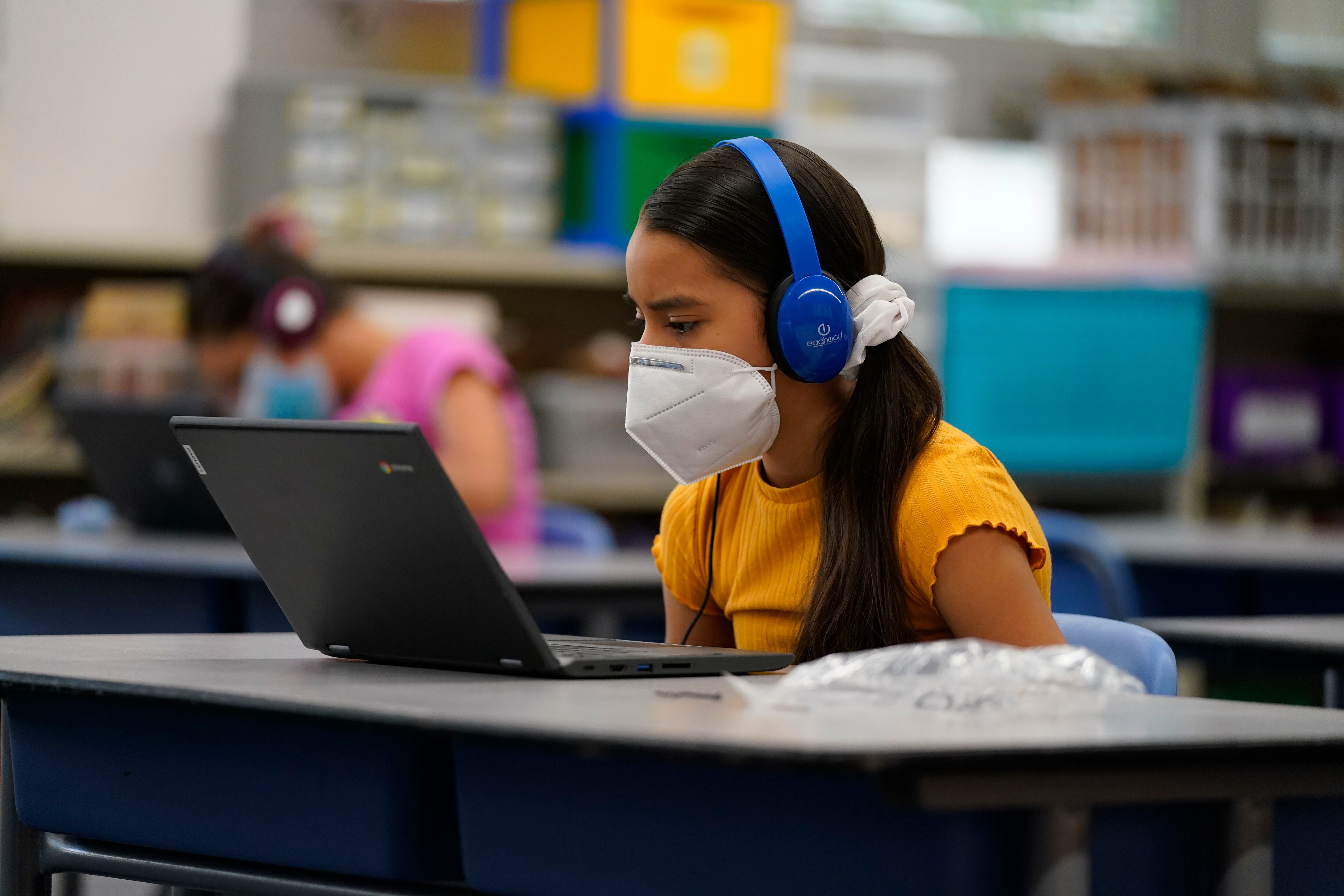

Many parents and educators assume Newark students experienced similar learning loss after classrooms closed last spring, considering that some students went months without being able to access online classes and some teachers only started giving live video lessons this fall. The district made remote learning more rigorous this school year, but also repeatedly postponed in-person learning as coronavirus cases remain high in Newark.

“Kids are very adaptive, but nothing’s ever going to be like when we’re in the classroom,” said fourth-grade teacher Wirmarie Morales. Her students have grown more comfortable with online learning and made academic progress, yet she still feels they would learn more in person. “There’s no way we’re not going to have some loss not having that school setting.”

But exactly how much learning was lost is an open question.

The challenge is that Newark has limited pre-pandemic data to use as a baseline. Like other states, New Jersey canceled its annual standardized tests last spring and could potentially do so again this year. Newark is administering a separate assessment, called MAP Growth, to track students’ progress this year. But because students did not take that test in 2019, it can’t offer a picture of student learning before and after classrooms closed.

The district does have other measures of student performance, such as attendance rates and course grades. But schools have relaxed their attendance and grading policies so much during remote learning that the data provides an incomplete or even skewed picture.

Despite the limited data, Newark is moving forward with plans to combat learning loss. The district has started to roll out some tutoring programs, though officials have not said what the tutoring entails or how many students are served. And the school board last month approved plans to apply for a state grant to offer in-person summer math classes for rising fourth and fifth graders.

“Part of the strategy here is not to assume that there will be loss, but to assume that we actually can do something about it right now,” Superintendent Roger León told the board in December, without going into detail about the district’s plans.

District spokesperson Nancy Deering did not answer questions about how the district is measuring or trying to mitigate learning loss.

The state also is working with limited data. The New Jersey education department created optional diagnostic tests, which 81 districts and eight schools for students with disabilities administered this fall. Still, most districts used different assessments, making it difficult to determine which districts and student populations lost the most ground during remote learning.

A bill, which is in the state Assembly after clearing the Senate, would require the state to collect student achievement data from every district and compile a report quantifying the pandemic’s academic impact. The report would break down outcomes by race, gender, income, and special needs.

“When we get objective, statewide data, we can see as a whole how we’re serving students in New Jersey,” said Patricia Morgan, executive director of JerseyCan, a group that supports student testing. “We really need that statewide data to know where to direct resources.”

Critics say the state should focus on patching up learning gaps. Schools already are assessing student progress and don’t need statewide tests this spring, which would consume instructional time and provide unreliable data because many students would take the tests remotely, say groups representing New Jersey teachers and administrators. Instead, they say what schools need are resources to support struggling students and accelerate learning.

“Now is the time for the New Jersey Department of Education to provide some essential tools and a vision and a plan for moving forward, not leaving every district to reinvent the wheel,” said Patricia Wright, executive director of the New Jersey Principals and Supervisors Association, at last week’s legislative meeting.

The state says help is on the way.

The Education Department will soon award grants for programs aimed at combating learning loss. However, the $2.5 million grant program will only include 16 districts — or about 2% of the total.

The state is set to receive another $1.2 billion in federal funds for K-12 schools through the stimulus package that Congress passed in December. (President Joe Biden has proposed another package with $130 billion more for schools, which lawmakers still must approve.)

New Jersey officials say they will give the bulk of the $1.2 billion to districts to use for pandemic response and recovery efforts. The state will use a portion of the money to fund research-based programs aimed at addressing learning loss, such as individual tutoring, extended learning time, and teacher training.

“Our understanding from the research and what we’re gleaning from school districts is that every student in the state has lost ground,” acting Education Commissioner Allen-McMillan told lawmakers. “So how can we help everyone move forward?”

Amber Brown, whose daughter is a third grader at Harriet Tubman School, said it’s undeniable that some students have fallen behind.

Brown withdrew from college this school year so she could focus on her daughter’s remote learning. But she notices during online lessons that some of her daughter’s classmates don’t have family members around to answer their questions and help them concentrate.

“When they were in virtual learning, did they understand what they learned?” she said. “We won’t know until they get back in the classroom.”