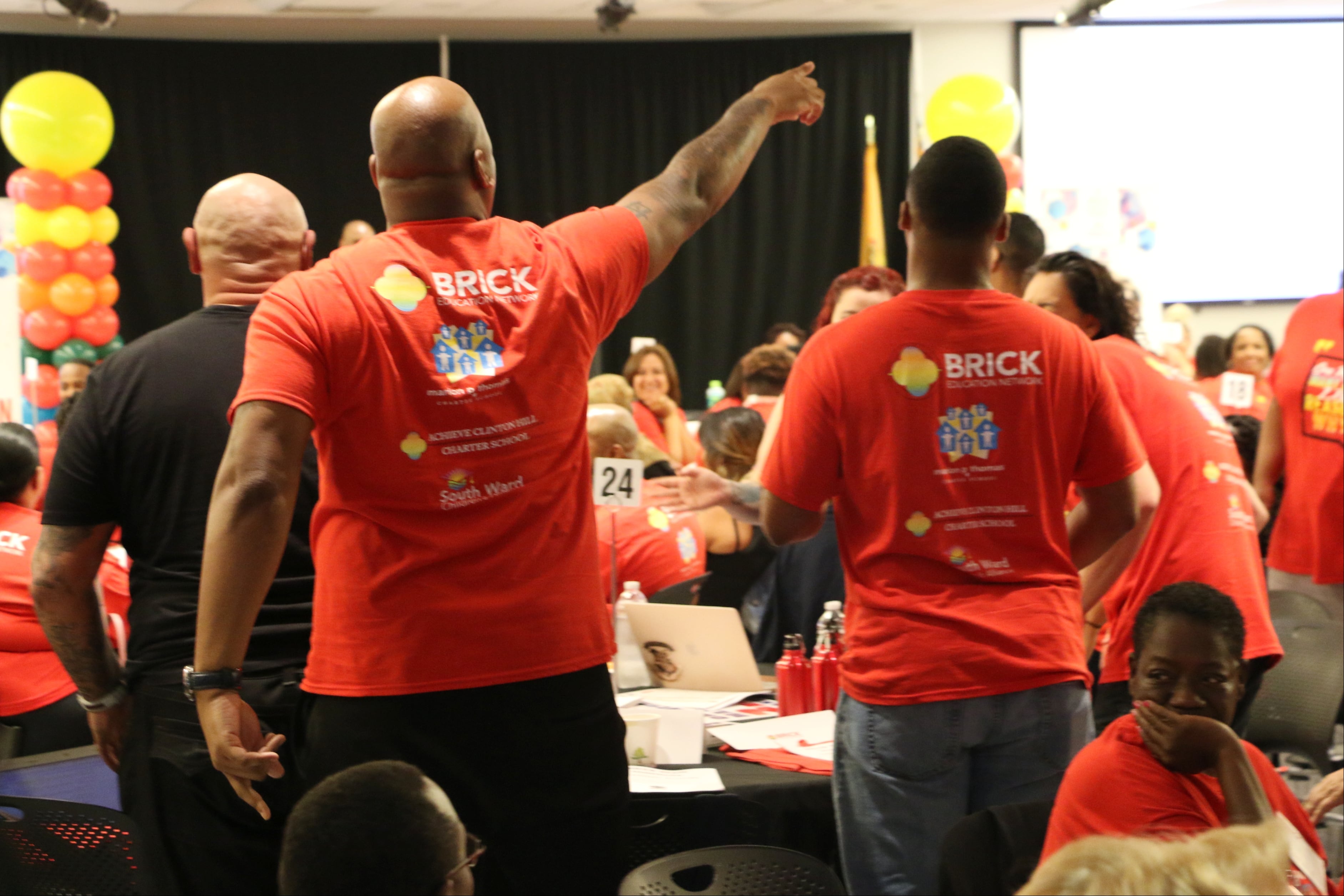

It was a hopeful day for the children of Newark, Rev. Vincent Rouse told a crowd of educators one August morning in 2019.

Marion P. Thomas, the decades-old network of Newark charter schools that Rouse oversees as board chair, was joining forces with the BRICK Education Network, a Newark-based school management group. The charter network would give BRICK a portion of its public funding to manage its schools, with the expectation that BRICK would help the struggling network avert financial and academic disaster.

“I trust you, BRICK. I trust you, Marion P.,” said Rouse, whose own children attend the schools, on that summer morning during the organizations’ first joint training. “Our babies are in your hands.”

Now, less than two years later, the partnership is falling apart.

BRICK CEO Dominique Lee and some school staffers say the nonprofit has stabilized the schools and steered the network through the pandemic. But Rouse and other Marion P. Thomas board members claim BRICK has usurped their authority and failed to deliver on its promises. At a contentious public meeting Monday where Rouse barred Lee from speaking, the board voted not to renew its contract with BRICK after it ends in June.

“The board was essentially ignored at times and in many ways couldn’t do anything,” Rouse said at the meeting. “Changes that were promised never materialized.”

BRICK’s leadership is hopeful that the partnership can be mended. But if not, both groups could face big challenges.

BRICK, which received a $10.5 million federal grant to open more of its own schools and turn around Marion P. Thomas, would lose a major funding stream and see its reach diminished. And the charter network, which was floundering before BRICK’s arrival, would undergo a seismic restructuring and leadership change during a pandemic that already has disrupted students’ lives and learning.

“They’re already falling behind as is,” said LaSonya Nevius, whose daughter attends one of the charter schools, during Monday’s meeting. “I just want to make sure they stay on the right path.”

Marion P. Thomas was in serious trouble when it brought in BRICK.

The network, which began in a church basement in 1999 and now includes two elementary schools and a high school, suffered from low test scores, a suspension rate three times the state average, and rampant teacher turnover. The state had targeted the schools for improvement, and the network had been forced to lay off employees and cut its summer programs to balance its budget.

BRICK said it could help turn things around. Formed in 2010 by a group of Newark teachers, BRICK had overseen improvements at two low-performing district schools and founded Achieve Charter School in Newark’s South Ward. It also oversees the South Ward Promise Neighborhood, a network of agencies that received a $30 million federal grant to provide social services to families in that high-needs section of Newark.

In April 2019, Rouse and the other Marion P. Thomas board members approved an agreement that made BRICK the network’s “charter management organization.” In return for 9% of the network’s annual public funding, or about $2.7 million last fiscal year, BRICK would manage the schools’ academics, finances, operations, hiring, and marketing.

Rouse was chair of the board when it approved the deal. (The previous chair, Greg Collins, who helped arrange the deal, had to step down before the vote because BRICK hired him as its chief financial officer.) Yet Rouse now says he didn’t realize how much control the network was handing over to the management firm.

“My understanding was that it would be assistance and not a full-fledged takeover,” he said in an interview Wednesday.

BRICK did make major changes. Together with the network’s former superintendent, A. Robert Gregory, BRICK introduced a new curriculum and teaching guides, hired a new corps of school administrators, revamped the schools’ discipline policies, took over most of the network’s central-office functions, and doubled the number of teachers in the lower grades.

Lee, the BRICK Education Network founder and CEO, told Chalkbeat the overhaul was working. The schools are suspending far fewer students, enrollment has grown, students were showing academic progress before the pandemic, and the network now has a budget surplus rather than a deficit, Lee said, citing internal data.

“Things were moving in the right direction,” he said this week. (The state has not publicly released data from last school year, BRICK’s first managing the network.)

Many staff members appear to agree. In an anonymous staff survey conducted in December, the majority of employees called the network a positive place to work and said they felt respected. In comments, they praised BRICK’s curriculum materials and training — a sentiment echoed at Monday’s board meeting.

“Our teachers have benefitted so much from the coaching and all of the extra support in our classrooms,” second-grade teacher Jessica Tsvang told the board. She was one of nearly two dozen educators and parents who spoke during a public comment period at the end of the virtual meeting — after the board already had voted to end BRICK’s contract.

But complaints about BRICK also emerged. In the surveys, employees said they were overworked, that BRICK’s management style could be top-down and rigid, and that the academic program had not been adequately adjusted for remote learning.

Rouse and some board members aired their own grievances this week. They said BRICK has not shared critical information with the board, prevented the network superintendent from making key decisions, and failed to make much-needed improvements to the special education program and the high school. More than 73% of ninth graders failed at least one class during the first part of this school year, a vice principal said Monday.

In an interview, Lee acknowledged that the high school needs major improvement, but said it was in worse shape before BRICK arrived. He also said board members only receive certain information because they are in charge of network governance and not management, the superintendent does have decision-making authority, and BRICK invested in online learning programs during the pandemic.

BRICK also has raised money for the charter network and supported families through the South Ward Promise Neighborhood, Lee added. During the pandemic, the organization delivered food to families and helped them pay rent, and handed out hundreds of toys and gift cards during the holidays.

Noting that BRICK and Marion P. Thomas are both proudly led by African Americans, Lee said he is optimistic the board will strike a new deal with BRICK.

“Hopefully they see the value of what we bring to the table,” he said, “and we’re just talking about changing things at the margins and not throwing out the baby with the bathwater.”

But the charter schools’ board has previewed plans for a full reorganization.

It is conducting a search for a new superintendent, and will form a committee to guide its “transition back to self-control,” according to a board resolution passed Monday. A board document said a majority of members want to reclaim control of most aspects of the network, which would strip BRICK of “nearly all of its responsibilities.”

If the plans come to pass, the board will have to replace the network’s management without jeopardizing what progress the schools have made — all during a pandemic that has left teachers and families craving stability and many students in desperate need of support.

“How do our children get the proper education,” parent Nikita Cuffie said in written comments during Monday’s board meeting, “when everytime we turn around something new is changing unexpectedly.”