If you wanted to keep up with Wilhelmina Holder, you had to move fast.

The Newark grandmother, parent organizer, student mentor, education activist, and self-described “lifelong learner” was always heading somewhere, talking to someone, planning something. And whether she was setting officials straight at a school board meeting, cornering a superintendent to raise some urgent matter, or prodding a high schooler to hit the books, she did not waste time equivocating. She told it like it was.

“That’s how I am these days — I have less of a filter,” she told me when we spoke last week, just days before her family on Sunday announced her death, at age 70.

Holder kept it real, but she also kept it joyful. She was fiercely serious about improving education for every young person, but playful in her approach. During our conversation last Thursday, she told me how she had been criticizing some policy or politician the other day when her daughter jokingly said she sounded like a bully. Holder thought that was hilarious.

“I’m going to be the senior bully,” she told me, punctuating that with her signature, rollicking laugh. “And guess what: I don’t give a damn who don’t like it!”

In the hours and days since her death, social media has overflowed with tributes to “Mrs. Holder,” “Mimi,” the “community mom.” She made those around her feel cared for and appreciated, energized, and inspired.

“She just supported all of us in growing in our voice,” said Kaleena Berryman, former executive director of the Abbott Leadership Institute, a group that teaches parents about education policy and activism. Holder was active in the group since its inception. “She was our example of youth advocacy and parent advocacy and working unapologetically for children.”

That, perhaps, is the heart of Holder’s legacy. She didn’t just fight for the rights of parents and students — she also galvanized countless others, through her example and encouragement, to take up the fight themselves.

One lesson she modeled for would-be activists: Keep showing up.

She rarely missed one of the Abbott Leadership Institute’s Saturday workshops; just last week, she led a training for parents on social-emotional learning. She was a fixture at school board meetings, and continued to work with families at West Side High School long after her daughters had graduated and her stint as PTA president had ended.

“She was the embodiment of that: consistent community activism and organizing,” said Bashir Muhammad Ptah Akinyele, a history and Africana studies teacher at Weequahic High School, Holder’s alma mater. “That was Wilhelmina Holder.”

After New Jersey took control of the Newark school system in 1995, Holder demanded that state officials — seen by some as an occupying force — listen to the concerns of families. When one state-appointed superintendent, Cami Anderson, announced a plan that involved closing some schools and putting charter school operators in charge of others, she helped lead a boycott of the district. “Keep your children home,” she urged parents.

“She was a warrior,” said Junius Williams, who helped found the Abbott Leadership Institute and was close friends with Holder. “She didn’t take no stuff from anyone in authority.”

In 2018, the state began transitioning the Newark school district back to local control. As the threat of school closures dissipated, and the elected school board chose a well-known Newark educator to become superintendent, the protests died down and attendance at school board meetings sagged.

But Holder kept showing up. She demanded that the board release details about the system used to assign students to school, urged officials to support overburdened comprehensive high schools, and, more recently, called for aggressive action to help students recover from pandemic learning loss.

“I don’t know how deeply we are aware of the fact that they need support — more than the lip service that some of them have been given,” she told the school board last November.

She was quick to add that she assumed good intentions on the part of officials and administrators. But she also wasn’t going to accept vague assurances that “something” was being done to catch students up.

“What is actually going on and how impactful is that for the students?” she said during the online board meeting. “See, I need someone to understand data, impact, and outcomes.”

Many times over the years, after I’d written about attendance rates or test scores or the opportunities students were — or weren’t — receiving, I would get a call from Holder: Can you share the data?

She wanted evidence of what was happening in the city’s schools and the effect on students. That was the essence of her advocacy: It wasn’t to gain recognition or engage in endless debates — it was to improve outcomes for children.

“What are we doing this work for if we can’t get kids access to a better life?” she once said to me.

Expecting greatness

She pushed elected officials, parents, and, in particular, students to do more, to be better, because she believed they were capable of so much. That belief had been ingrained in her growing up in Newark in the 1950s and 60s in a family of six children.

“Even though I came out of a home that had lower socio-economic status, my mother and father had certain expectations of us and so did all the people in their circle, all the people in my church,” she told me, adding that their message to her was clear: “You’re very smart, you’re going to college.”

In high school, Holder submitted poems to the school newspaper. Decades later, her passion for language spurred her to become an advocate for better schools when, as a volunteer at the Boys & Girls Club, she noticed that an alarming number of children had trouble reading and writing.

“I used to complain a lot about that to the director and other volunteers,” she recalled in an interview last year. “One of them, my dear friend, said to me, ‘Well do something about it.’”

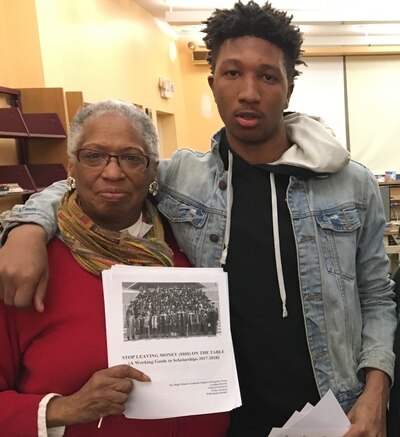

She did. With Lyndon Brown, she helped run the High School Academic Support Program, which for more than three decades has helped prepare thousands of Newark students for college. She spent countless hours reading and revising students’ personal essays, and accompanying them on college visits.

One of the first times I spoke with Holder was in March 2018 at a college fair that she and Brown organized on the second floor of the Springfield branch of the Newark Public Library. Hundreds of students turned out for it.

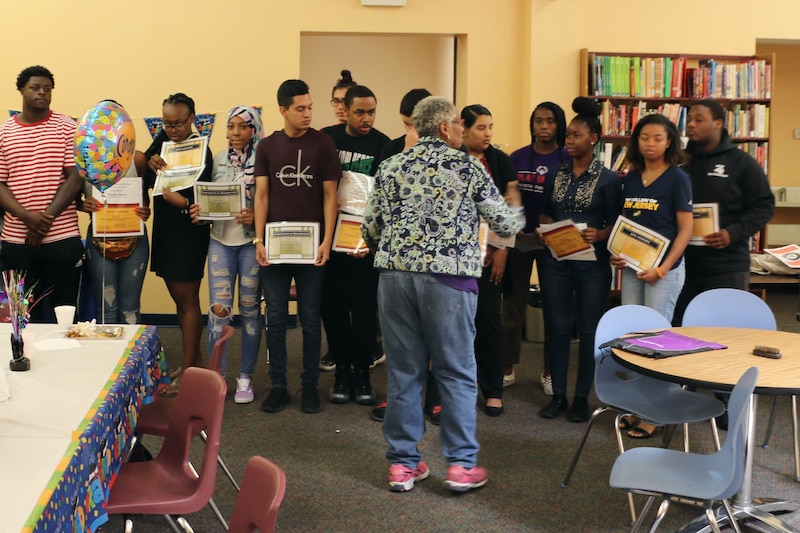

I returned to the library a year later to attend a graduation ceremony that Brown and Holder held for the students in their free college-prep program. The pair and their helpers had decorated the room with balloons and photos of the students, brought fried chicken and cake, and handed out “certificates of excellence.” At one point, Holder lined the teens up for a photo.

“Smile, we’re so proud of you,” she told them. “You are great students, and we expect great things from you.”

Holder expected great things from a lot of people. She believed in the innate greatness of the children and adults of Newark, which she made it her mission to unleash.

“One of the main things she taught me was that everyone has a purpose,” said Omayra Molina, whom Holder raised as her daughter. “Her purpose was to come in and change the community, one person at a time.”

A few years ago, I watched Holder speak at a school board meeting held in the basement of the school district’s downtown headquarters.

She commended a principal who worked closely with parents, then raised concerns about the high schools and asked for more data. She kept speaking even after her allotted three minutes ended and someone cut off her microphone.

On the way back to her seat, she added for all to hear: “I’ll be here every month until God calls me home.”

She kept her word.

Patrick Wall is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, covering public education in the city and across New Jersey. Contact Patrick at pwall@chalkbeat.org.